Achilles tendinitis is a common condition that causes pain along the back of the leg near the heel.

The Achilles tendon is the largest tendon in the body. It connects your calf muscles to your heel bone and is used when you walk, run, and jump.

Although the Achilles tendon can withstand great stresses from running and jumping, it is also prone to tendinitis, a condition associated with overuse and degeneration.

Description

Simply defined, tendinitis is inflammation of a tendon. Inflammation is the body’s natural response to injury or disease, and often causes swelling, pain, or irritation. There are two types of Achilles tendinitis, based upon which part of the tendon is inflamed.

Noninsertional Achilles tendinitis

Noninsertional Achilles Tendinitis

In noninsertional Achilles tendinitis, fibers in the middle portion of the tendon have begun to break down with tiny tears (degenerate), swell, and thicken.

Tendinitis of the middle portion of the tendon more commonly affects younger, active people.

Insertional Achilles Tendinitis

Insertional Achilles tendinitis involves the lower portion of the heel, where the tendon attaches (inserts) to the heel bone.

In both noninsertional and insertional Achilles tendinitis, damaged tendon fibers may also calcify (harden). Bone spurs (extra bone growth) often form with insertional Achilles tendinitis.

Tendinitis that affects the insertion of the tendon can occur at any time, even in patients who are not active.

Insertional Achilles tendinitis

Cause

Achilles tendinitis is typically not related to a specific injury. The problem results from repetitive stress to the tendon. This often happens when we push our bodies to do too much, too soon, but other factors can make it more likely to develop tendinitis, including:

A bone spur that has developed where the tendon attaches to the heel bone.

- Sudden increase in the amount or intensity of exercise activity—for example, increasing the distance you run every day by a few miles without giving your body a chance to adjust to the new distance

- Tight calf muscles—Having tight calf muscles and suddenly starting an aggressive exercise program can put extra stress on the Achilles tendon

- Bone spur—Extra bone growth where the Achilles tendon attaches to the heel bone can rub against the tendon and cause pain

Symptoms

Common symptoms of Achilles tendinitis include:

- Pain and stiffness along the Achilles tendon in the morning

- Pain along the tendon or back of the heel that worsens with activity

- Severe pain the day after exercising

- Thickening of the tendon

- Bone spur (insertional tendinitis)

- Swelling that is present all the time and gets worse throughout the day with activity

If you have experienced a sudden “pop” in the back of your calf or heel, you may have ruptured (torn) your Achilles tendon. See your doctor immediately if you think you may have torn your tendon.

Examination

After you describe your symptoms and discuss your concerns, the doctor will examine your foot and ankle. The doctor will look for these signs:

- Swelling along the Achilles tendon or at the back of your heel

- Thickening or enlargement of the Achilles tendon

- Bony spurs at the lower part of the tendon at the back of your heel (insertional tendinitis)

- The point of maximum tenderness

- Pain in the middle of the tendon, (noninsertional tendinitis)

- Pain at the back of your heel at the lower part of the tendon (insertional tendinitis)

- Limited range of motion in your ankle—specifically, a decreased ability to flex your foot

Tests

Your doctor may order imaging tests to make sure your symptoms are caused by Achilles tendinitis.

X-rays

X-ray tests provide clear images of bones. X-rays can show whether the lower part of the Achilles tendon has calcified, or become hardened. This calcification indicates insertional Achilles tendinitis. In cases of severe noninsertional Achilles tendinitis, there can be calcification in the middle portion of the tendon, as well.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not necessary to diagnose Achilles tendinitis, it is important for planning surgery. An MRI scan can show how severe the damage is in the tendon. If surgery is needed, your doctor will select the procedure based on the amount of tendon damage.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

In most cases, nonsurgical treatment options will provide pain relief, although it may take a few months for symptoms to completely subside. Even with early treatment, the pain may last longer than 3 months. If you have had pain for several months before seeking treatment, it may take 6 months before treatment methods take effect.

Rest. The first step in reducing pain is to decrease or even stop the activities that make the pain worse. If you regularly do high-impact exercises (such as running), switching to low-impact activities will put less stress on the Achilles tendon. Cross-training activities such as biking, elliptical exercise, and swimming are low-impact options to help you stay active.

Ice. Placing ice on the most painful area of the Achilles tendon is helpful and can be done as needed throughout the day. This can be done for up to 20 minutes and should be stopped earlier if the skin becomes numb. A foam cup filled with water and then frozen creates a simple, reusable ice pack. After the water has frozen in the cup, tear off the rim of the cup. Then rub the ice on the Achilles tendon. With repeated use, a groove that fits the Achilles tendon will appear, creating a “custom-fit” ice pack.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Drugs such as ibuprofen and naproxen reduce pain and swelling. They do not, however, reduce the thickening of the degenerated tendon. Using the medication for more than 1 month should be reviewed with your primary care doctor.

Exercise. The following exercise can help to strengthen the calf muscles and reduce stress on the Achilles tendon.

- Calf stretch

Lean forward against a wall with one knee straight and the heel on the ground. Place the other leg in front, with the knee bent. To stretch the calf muscles and the heel cord, push your hips toward the wall in a controlled fashion. Hold the position for 10 seconds and relax. Repeat this exercise 20 times for each foot. A strong pull in the calf should be felt during the stretch.

Physical Therapy. Physical therapy is very helpful in treating Achilles tendinitis. It has proven to work better for noninsertional tendinitis than for insertional tendinitis.

Eccentric Strengthening Protocol. Eccentric strengthening is defined as contracting (tightening) a muscle while it is getting longer. Eccentric strengthening exercises can cause damage to the Achilles tendon if they are not done correctly. At first, they should be performed under the supervision of a physical therapist. Once mastered with a therapist, the exercises can then be done at home. These exercises may cause some discomfort, however, it should not be unbearable.

-

- Bilateral heel drop

Stand at the edge of a stair, or a raised platform that is stable, with just the front half of your foot on the stair. This position will allow your heel to move up and down without hitting the stair. Care must be taken to ensure that you are balanced correctly to prevent falling and injury. Be sure to hold onto a railing to help you balance.

Lift your heels off the ground then slowly lower your heels to the lowest point possible. Repeat this step 20 times. This exercise should be done in a slow, controlled fashion. Rapid movement can create the risk of damage to the tendon. As the pain improves, you can increase the difficulty level of the exercise by holding a small weight in each hand.

- Single leg heel drop

This exercise is performed similarly to the bilateral heel drop, except that all your weight is focused on one leg. This should be done only after the bilateral heel drop has been mastered.

Cortisone injections. Cortisone, a type of steroid, is a powerful anti-inflammatory medication. Cortisone injections into the Achilles tendon are rarely recommended because they can cause the tendon to rupture (tear).

Supportive shoes and orthotics. Pain from insertional Achilles tendinitis is often helped by certain shoes, as well as orthotic devices. For example, shoes that are softer at the back of the heel can reduce irritation of the tendon. In addition, heel lifts can take some strain off the tendon.

Heel lifts are also very helpful for patients with insertional tendinitis because they can move the heel away from the back of the shoe, where rubbing can occur. They also take some strain off the tendon. Like a heel lift, a silicone Achilles sleeve can reduce irritation from the back of a shoe.

If your pain is severe, your doctor may recommend a walking boot for a short time. This gives the tendon a chance to rest before any therapy is begun. Extended use of a boot is discouraged, though, because it can weaken your calf muscle.

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT). During this procedure, high-energy shockwave impulses stimulate the healing process in damaged tendon tissue. ESWT has not shown consistent results and, therefore, is not commonly performed.

ESWT is noninvasive—it does not require a surgical incision. Because of the minimal risk involved, ESWT is sometimes tried before surgery is considered.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery should be considered to relieve Achilles tendinitis only if the pain does not improve after 6 months of nonsurgical treatment. The specific type of surgery depends on the location of the tendinitis and the amount of damage to the tendon.

Gastrocnemius recession. This is a surgical lengthening of the calf (gastrocnemius) muscles. Because tight calf muscles place increased stress on the Achilles tendon, this procedure is useful for patients who still have difficulty flexing their feet, despite consistent stretching.

In gastrocnemius recession, one of the two muscles that make up the calf is lengthened to increase the motion of the ankle. The procedure can be performed with a traditional, open incision or with a smaller incision and an endoscope—an instrument that contains a small camera. Your doctor will discuss the procedure that best meets your needs.

Complication rates for gastrocnemius recession are low, but can include nerve damage.

Gastrocnemius recession can be performed with or without débridement, which is removal of damaged tissue.

Débridement and repair (tendon has less than 50% damage). The goal of this operation is to remove the damaged part of the Achilles tendon. Once the unhealthy portion of the tendon has been removed, the remaining tendon is repaired with sutures, or stitches to complete the repair.

In insertional tendinitis, the bone spur is also removed. Repair of the tendon in these instances may require the use of metal or plastic anchors to help hold the Achilles tendon to the heel bone, where it attaches.

After débridement and repair, most patients are allowed to walk in a removable boot or cast within 2 weeks, although this period depends upon the amount of damage to the tendon.

Débridement with tendon transfer (tendon has greater than 50% damage). In cases where more than 50% of the Achilles tendon is not healthy and requires removal, the remaining portion of the tendon is not strong enough to function alone. To prevent the remaining tendon from rupturing with activity, an Achilles tendon transfer is performed. The tendon that helps the big toe point down is moved to the heel bone to add strength to the damaged tendon. Although this sounds severe, the big toe will still be able to move, and most patients will not notice a change in the way they walk or run.

Depending on the extent of damage to the tendon, some patients may not be able to return to competitive sports or running.

Recovery. Most patients have good results from surgery. The main factor in surgical recovery is the amount of damage to the tendon. The greater the amount of tendon involved, the longer the recovery period, and the less likely a patient will be able to return to sports activity.

Physical therapy is an important part of recovery. Many patients require 12 months of rehabilitation before they are pain-free.

Complications. Moderate to severe pain after surgery is noted in 20% to 30% of patients and is the most common complication. In addition, a wound infection can occur and the infection is very difficult to treat in this location.

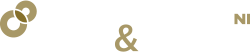

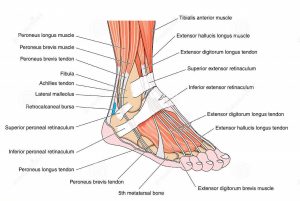

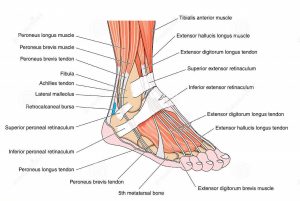

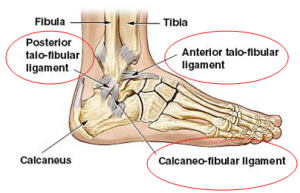

The ankle joint is a hinge between the leg and the foot. The bones of the leg (tibia and fibula) form a sort of slot and the curved top bone of the foot (talus) fits between them. The talus is held to the tibia and fibula by strong bands of tissue called ligaments. Each ligament is made of many strands or fibres of a material called collagen, which is extremely strong.

The ligament on the inside of the ankle (medial or deltoid ligament) has two layers; the deepest one is most important. This ligament is mainly torn in association with severe fractures of the ankle bones.

The ligament on the outside of the ankle (lateral ligament) is made up of three separate bands: one at the front (anterior talo-fibular ligament), one in the middle (calcaneo-fibular ligament) and one at the back (posterior talo-fibular ligament). The front band is the usual ligament injured in sprains or tears of the ankle ligaments, and the middle band is sometimes affected.

The tibia and fibula have a small joint between themselves just above the ankle. This also has strong ligaments, one at the front and one at the back. (tibio-fibular ligaments). The ligament at the front is involved in 10-20% of ankle sprains; the ligament at the back, like the deltoid ligament, is mainly damaged in association with severe fractures of the ankle bones.

How do they get injured?

Most ankle ligament injuries are caused when the foot twists so that the sole is pointing inwards (inversion), usually when the foot is pointing downwards rather than flat on the ground. When this happens, the full force of the body’s movement is placed on the anterior talo-fibular ligament. This may stretch, with tearing of some of its fibres (sprain) or it may tear completely. If there is a major injury of the anterior talo-fibular ligament, the forces transfer to the calcaneo-fibular ligament and the tibio-fibular ligaments, which may also be sprained or torn. Occasionally small pieces of bone may be torn off with the ligaments.

In a few cases, a twisting force on the ankle may cause other damage. The bones around the ankle may be broken, a piece of the joint surface inside the ankle may be chipped off, ligaments connecting other bones in the foot may be sprained or torn, or the tendons around the ankle may be damaged.

What should I do if I sprain my ankle?

Most ankle sprains are fairly minor injuries which will get better with simple self-care treatment. The word RICE reminds us of the basic treatment of a sprained joint:

- Rest take the weight off the injured joint as much as possible for a day or two

- Ice an ice pack (a small bag of frozen peas or corn is ideal) can be applied for 10-15 minutes 3-4 times a day to reduce swelling

- Compression a firm bandage or strapping will help to get swelling down

- Elevation resting with the ankle above the height of the body will allow swelling to drain away into the bloodstream

Although a couple of days rest is useful, it is best to start taking some weight on the injured ankle reasonably soon after injury, usually within 2-3 days. Also start to exercise and stretch the injured ankle as soon as possible after the injury.

Normally a sprained ankle will recover within 6-8 weeks, although it may tend to swell for a few weeks longer.

When should I go to casualty?

Basically, if you have a severe ankle injury it is best to get professional advice immediately. Things that suggest a severe injury include:

- your ankle is so painful you cannot bear any weight on it

- the ankle seems deformed

- the skin over the ankle is broken

- the injury was caused by a severe force such as a fall from a height or a blow from a heavy object

- the pain and swelling seem to get worse rather than better over the first 3-4 days (the bruising often gets worse for a week or more before it starts to fade)

Should I have physiotherapy?

Most simple sprains get better without any special treatment. However, if you have a severe injury or the initial injury does not recover normally, it is usually best to see a physiotherapist. The hospital casualty or orthopaedic department, your own GP or your sports club can arrange this. Physiotherapists also advertise in Yellow Pages and local papers.

Length of Recovery

Most ankle injuries get better completely and cause no long-term problems. Sometimes, however, there is some permanent damage to the ankle. The ligaments may fail to heal properly and become weak, or there may be damage to the joint itself or some other structure nearby.

Most importantly, an ankle ligament injury also damages the small nerve endings in the joint and ligaments. These endings are very important, as they tell your brain where your ankle is and what position it is in (they are called “proprioceptive nerves”). Your brain relies on this information to control the muscles which move and protect your ankle. If these nerve endings are not working properly, your brain does not get reliable information and the muscles around your ankle may not work together properly. You would feel this as a tendency for your ankle to “give way”, often with minor stresses. This might make you prone to repeated ankle sprains. This is referred to as “ankle instability” and is more commonly due to damage to the proprioceptive nerves than actual weakness of the ligaments.

How would ankle instability be diagnosed?

Your doctor or physiotherapist will listen to your complaints about your ankle and examine you. They will try to see if there is anything, which makes you more liable to ankle instability than average. They will look for any sign that you have some other problem around your ankle, such as damage to the joint surface. They will stretch your ankle in various directions to see if the ligaments are abnormally weak.

An Xray will usually be taken to see if there is any damage to the bones of your ankle. Ligaments do not show on Xrays. Ligament damage can be shown by taking Xrays with your ankle stretched in various directions (“stress views”), by injecting dye into your ankle or around a neighbouring tendon, or with a magnetic (MRI) scan. However, these special tests are usually not needed at first.

What can be done about ankle instability?

As most people with ankle instability have proprioceptive nerves which are not working properly, the first treatment is a physiotherapy programme to re-train these nerves how to respond to movements of the ankle, by doing various exercises and activities. If your ankle or Achilles tendon are stiff, you will also be shown exercises to stretch these, and the strength of the muscles around the ankle will be increased by exercises. If your foot shape makes you prone to extra stress on the ankle ligaments, a moulded insole may be advised for your shoe to reduce these stresses.

Many people will find their ankle much more stable and comfortable after physiotherapy. However, in some people problems continue. At this point the opinion of an orthopaedic foot and ankle surgeon would be helpful. If you have not already had the special tests mentioned above, these may be done now. The surgeon may also suggest an exploratory operation on your ankle (arthroscopy) to check on the state of the joint. If these tests suggest weakness of the ankle ligaments, an operation may be advised.

Will I need an operation?

Most people with ankle instability will not need an operation. Even if your ankle still feels unstable after physiotherapy, you could try a brace rather than having an operation to tighten up or replace the ligaments.

However, if no other treatment makes your ankle comfortable and tests show that the ligaments are weak, an operation may help. There are two main types of operation:

- the damaged ligaments are tightened up and re-attached to the bone – often known as the Brostrum procedure. This is suitable when the instability is not too severe. Its main advantage is that it causes less stiffness than the other type of repair, as it aims to achieve an anatomical repair of the ligaments.

- another piece of tissue, usually part of one of the nearby tendons, is borrowed and stitched between the bones where the ligaments should be. This is suitable when the instability is severe or you may put severe stresses on the repair. It is very strong but often causes quite a lot of stiffness in the ankle afterwards.

You would usually be in a plaster or brace for several weeks after an operation and would need further physiotherapy to help regain normal function.

The other problems which may occur after a ligament reconstruction operation include:

- pain in the ankle, either because of damage at the time of the original injury or because the ankle is now tighter than before

- numbness or tingling down the side of the foot due to stretching of one of the nerves either at the time of the original injury or the operation

- persistent swelling of the ankle

A bunion is a painful bony bump that develops on the inside of the foot at the big toe joint. Bunions are often referred to as hallux valgus.

Bunions develop slowly. Pressure on the big toe joint causes the big toe to lean toward the second toe. Over time, the normal structure of the bone changes, resulting in the bunion bump. This deformity will gradually increase and may make it painful to wear shoes or walk.

Anyone can get a bunion, but they are more common in women. Many women wear tight, narrow shoes that squeeze the toes together—which makes it more likely for a bunion to develop, worsen and cause painful symptoms.

In most cases, bunion pain is relieved by wearing wider shoes with adequate toe room and using other simple treatments to reduce pressure on the big toe.

Bunions sometimes develop in both feet.

The big toe is made up of two joints. The largest of the two is the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP), where the first long bone of the foot (metatarsal) meets the first bone of the toe (phalanx).

Bunions develop at the MTP joint.

The metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint.

Description

A bunion forms when the bones that make up the MTP joint move out of alignment: the long metatarsal bone shifts toward the inside of the foot, and the phalanx bones of the big toe angle toward the second toe. The MTP joint gets larger and protrudes from the inside of the forefoot.

The MTP joint becomes enlarged and inflamed.

The enlarged joint is often inflamed. The word “bunion” comes from the Greek word for turnip, and the bump on the inside of the foot typically looks red and swollen like a turnip.

Bunion Progression

Bunions worsen over time. As the big toe angles toward the second toe, it can cross over it and cause additional problems.

Bunions start out small — but they usually get worse over time (especially if the individual continues to wear tight, narrow shoes). Because the MTP joint flexes with every step, the bigger the bunion gets, the more painful and difficult walking can become.

An advanced bunion can greatly alter the appearance of the foot. In severe bunions, the big toe may angle all the way under or over the second toe. Pressure from the big toe may force the second toe out of alignment, causing it to come in contact with the third toe. Calluses may develop where the toes rub against each other, causing additional discomfort and difficulty walking.

Foot Problems Related to Bunions

In some cases, an enlarged MTP joint may lead to bursitis, a painful condition in which the fluid-filled sac (bursa) that cushions the bone near the joint becomes inflamed. It may also lead to chronic pain and arthritis if the smooth articular cartilage that covers the joint becomes damaged from the joint not gliding smoothly.

Adolescent Bunion

In addition to the common bunion, there are other types of bunions. As the name implies, bunions that occur in young people are called adolescent bunions. These bunions are most common in girls between the ages of 10 and 15.

While a bunion on an adult often restricts motion in the MTP joint, a young person with a bunion can normally move the big toe up and down. An adolescent bunion may still be painful, however, and make it difficult to wear shoes.

As opposed to adult bunions — which usually are associated with long-term wear of narrow, tight shoes — adolescent bunions are often genetic and run in families.

Bunionette

A bunionette, or “tailor’s bunion,” occurs on the outside of the foot near the base of the little toe. Although it is in a different spot on the foot, a bunionette is very much like a bunion. You may develop painful bursitis and a hard corn or callus over the bump.

A bunion that forms in the main joint of the little toe is called a bunionette.

Cause

Bunions may be caused by:

- Wearing poorly fitting shoes—in particular, shoes with a narrow, pointed toe box that forces the toes into an unnatural position

- Heredity—some people inherit feet that are more likely to develop bunions due to their shape and structure

- Having an inflammatory condition, such as rheumatoid arthritis, or a neuromuscular condition, such as polio

Symptoms

In addition to the visible bump on the inside of the foot, symptoms of a bunion may include:

- Pain and tenderness

- Redness and inflammation

- Hardened skin on the bottom of the foot

- A callus or corn on the bump

- Stiffness and restricted motion in the big toe, which may lead to difficulty in walking

Examination

Physical Examination

Your doctor will ask you about your medical history, general health, and symptoms. He or she will perform a careful examination of your foot. Although your doctor will probably be able to diagnose your bunion based on your symptoms and on the appearance of your toe, he or she will also order an x-ray.

X-Rays

X-rays provide images of dense structures, such as bone. An x-ray will allow your doctor to check the alignment of your toes and look for damage to the MTP joint.

The alignment of your foot bones changes when you stand or sit. Your doctor will take an x-ray while you are standing in order to more clearly see the malalignment of the bones of your foot. He or she will use the x-rays to determine how severe the bunion is, and how best to correct it.

X-rays of your foot will show your doctor how far out of alignment the bones have become.

Nonsurgical Treatment

In most cases, bunions are treated without surgery. Although nonsurgical treatment cannot actually “reverse” a bunion, it can help reduce pain and keep the bunion from worsening.

Changes in Footwear

In the vast majority of cases, bunion pain can be managed successfully by switching to shoes that fit properly and do not compress the toes. Some shoes can be modified by using a stretcher to stretch out the areas that put pressure on your toes. Your doctor can give you information about proper shoe fit and the type of shoes that would be best for you. (See below section on “Tips for Proper Shoe Fit”)

Padding

Protective “bunion-shield” pads can help cushion the painful area over the bunion. Pads can be purchased at a drugstore or pharmacy. Be sure to test the pads for a short time period first; the size of the pad may increase the pressure on the bump. This could worsen your pain rather than reduce it.

Orthotics and Other Devices

To take pressure off your bunion, your doctor may recommend that you wear over-the-counter or custom-made shoe inserts (orthotics). Toe spacers can be placed between your toes. In some cases, a splint worn at night that places your big toe in a straighter position may help relieve pain.

Icing

Applying ice several times a day for 20 minutes at a time can help reduce swelling. Do not apply ice directly on your skin.

Medications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen and naproxen can help relieve pain and reduce swelling. Other medications can be prescribed to help pain and swelling in patients whose bunions are caused by arthritis.

When Is Bunion Surgery Needed?

Your doctor may recommend surgery for a bunion or bunionette if, after a period of time, you have pain and difficulty walking despite changes in footwear and other nonsurgical treatments. Bunion surgery realigns bone, ligaments, tendons, and nerves so that the big toe can be brought back to its correct position.

There are several surgical procedures to correct bunions. Although many are done on a same-day basis with no hospital stay, a long recovery is common after bunion surgery.

Surgery to remove an adolescent bunion is not recommended unless the bunion causes extreme pain that does not improve with a change in footwear or addition of orthotics. If an adolescent has bunion surgery, particularly before reaching skeletal maturity, there is a strong chance the bunion will return.

People often blame the common foot deformity claw toe on wearing shoes that squeeze your toes, such as shoes that are too short or high heels. However, claw toe also is often the result of nerve damage caused by diseases like diabetes or alcoholism, which can weaken the muscles in your foot. Having claw toe means your toes “claw,” digging down into the soles of your shoes and creating painful calluses. Claw toe gets worse without treatment and may become a permanent deformity over time.

- Your toes are bent upward (extension) from the joints at the ball of the foot.

- Your toes are bent downward (flexion) at the middle joints toward the sole of your shoe.

- Sometimes your toes also bend downward at the top joints, curling under the foot.

- Corns may develop over the top of the toe or under the ball of the foot.

Evaluation

If you have symptoms of a claw toe, see your doctor for evaluation. You may need certain tests to rule out neurological disorders that can weaken your foot muscles, creating imbalances that bend your toes. Trauma and inflammation can also cause claw toe deformity.

Treatment

Claw toe deformities are usually flexible at first, but they harden into place over time. If you have claw toe in early stages, your doctor may recommend a splint or tape to hold your toes in correct position. Additional advice:

- Wear shoes with soft, roomy toe boxes and avoid tight shoes and high-heels.

- Use your hands to stretch your toes and toe joints toward their normal positions.

- Exercise your toes by using them to pick up marbles or crumple a towel laid flat on the floor.

If you have claw toe in later stages and your toes are fixed in position:

- A special pad can redistribute your weight and relieve pressure on the ball of your foot.

- Try special “in depth” shoes that have an extra 3/8″ depth in the toe box.

- Ask a shoe repair shop to stretch a small pocket in the toe box to accommodate the deformity.

If these treatments do not help, you may need surgery to correct the problem.

Hammer Toe

A hammer toe is a deformity of the second, third or fourth toes. In this condition, the toe is bent at the middle joint, so that it resembles a hammer. Initially, hammer toes are flexible and can be corrected with simple measures but, if left untreated, they can become fixed and require surgery.

People with hammer toe may have corns or calluses on the top of the middle joint of the toe or on the tip of the toe. They may also feel pain in their toes or feet and have difficulty finding comfortable shoes.

Hammer toe results from shoes that don’t fit properly or a muscle imbalance, usually in combination with one or more other factors. Muscles work in pairs to straighten and bend the toes. If the toe is bent and held in one position long enough, the muscles tighten and cannot stretch out.

Shoes that narrow toward the toe may make your forefoot look smaller. But they also push the smaller toes into a flexed (bent) position. The toes rub against the shoe, leading to the formation of corns and calluses, which further aggravate the condition. A higher heel forces the foot down and squishes the toes against the shoe, increasing the pressure and the bend in the toe. Eventually, the toe muscles become unable to straighten the toe, even when there is no confining shoe.

Treatment

Conservative treatment starts with new shoes that have soft, roomy toe boxes. Shoes should be one-half inch longer than your longest toe. (Note: For many people, the second toe is longer than the big toe.) Avoid wearing tight, narrow, high-heeled shoes. You may also be able to find a shoe with a deep toe box that accommodates the hammer toe. Or, a shoe repair shop may be able to stretch the toe box so that it bulges out around the toe. Sandals may help, as long as they do not pinch or rub other areas of the foot.

Your doctor may also prescribe some toe exercises that you can do at home to stretch and strengthen the muscles. For example, you can gently stretch the toes manually. You can use your toes to pick things up off the floor. While you watch television or read, you can put a towel flat under your feet and use your toes to crumple it.

Finally, your doctor may recommend that you use commercially available straps, cushions or nonmedicated corn pads to relieve symptoms. If you have diabetes, poor circulation or a lack of feeling in your feet, talk to your doctor before attempting any self-treatment.

Hammer toe can be corrected by surgery if conservative measures fail. Usually, surgery is done on an outpatient basis with a local anesthetic. The actual procedure will depend on the type and extent of the deformity. After the surgery, there may be some stiffness, swelling and redness and the toe may be slightly longer or shorter than before. You will be able to walk, but should not plan any long hikes while the toe heals, and should keep your foot elevated as much as possible.

Heel Pain

Every mile you walk puts 60 tons of stress on each foot. Your feet can handle a heavy load, but too much stress pushes them over their limits. When you pound your feet on hard surfaces playing sports or wear shoes that irritate sensitive tissues, you may develop heel pain, the most common problem affecting the foot and ankle. A sore heel will usually get better on its own without surgery if you give it enough rest. However, many people try to ignore the early signs of heel pain and keep on doing the activities that caused it. When you continue to use a sore heel, it will only get worse and could become a chronic condition leading to more problems. Surgery is rarely necessary.

Heel pain can have many causes. If your heel hurts, see your doctor right away to determine why and get treatment. Tell him or her exactly where you have pain and how long you’ve had it. Your doctor will examine your heel, looking and feeling for signs of tenderness and swelling. You may be asked to walk, stand on one foot or do other physical tests that help your doctor pinpoint the cause of your sore heel.

Treatment

Conditions that cause heel pain generally fall into two main categories: pain beneath the heel and pain behind the heel.

Pain Beneath the Heel

If it hurts under your heel, you may have one or more conditions that inflame the tissues on the bottom of your foot:

- Stone bruise. When you step on a hard object such as a rock or stone, you can bruise the fat pad on the underside of your heel. It may or may not look discolored. The pain goes away gradually with rest.

- Plantar fasciitis (subcalcaneal pain). Doing too much running or jumping can inflame the tissue band (fascia) connecting the heel bone to the base of the toes. The pain is centered under your heel and may be mild at first but flares up when you take your first steps after resting overnight. You may need to do special exercises, take medication to reduce swelling and wear a heel pad in your shoe.

- Heel spur.When plantar fasciitis continues for a long time, a heel spur (calcium deposit) may form where the fascia tissue band connects to your heel bone. Your doctor may take an X-ray to see the bony protrusion, which can vary in size. Treatment is usually the same as for plantar fasciitis: rest until the pain subsides, do special stretching exercises and wear heel pad shoe inserts.

Pain Behind the Heel

If you have pain behind your heel, you may have inflamed the area where the Achilles tendon inserts into the heel bone (retrocalcaneal bursitis). People often get this by running too much or wearing shoes that rub or cut into the back of the heel. Pain behind the heel may build slowly over time, causing the skin to thicken, get red and swell. You might develop a bump on the back of your heel that feels tender and warm to the touch. The pain flares up when you first start an activity after resting. It often hurts too much to wear normal shoes. You may need an X-ray to see if you also have a bone spur.

Treatment includes resting from the activities that caused the problem, doing certain stretching exercises, using pain medication and wearing open back shoes.

- Your doctor may want you to use a 3/8″ or 1/2″ heel insert.

- Stretch your Achilles tendon by leaning forward against a wall with your foot flat on the floor and heel elevated with the insert.

- Use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications for pain and swelling.

- Consider placing ice on the back of the heel to reduce inflammation.

Ingrown Toenail

If you trim your toenails too short, particularly on the sides of your big toes, you may set the stage for an ingrown toenail. Like many people, when you trim your toenails, you may taper the corners so that the nail curves with the shape of your toe. But this technique may encourage your toenail to grow into the skin of your toe. The sides of the nail curl down and dig into your skin. An ingrown toenail may also happen if you wear shoes that are too tight or too short.

When you first have an ingrown toenail, it may be hard, swollen and tender. Later, it may get red and infected, and feel very sore. Ingrown toenails are a common, painful condition—particularly among teenagers. Any of your toenails can become ingrown, but the problem more often affects the big toe. An ingrown nail occurs when the skin on one or both sides of a nail grows over the edges of the nail, or when the nail itself grows into the skin. Redness, pain and swelling at the corner of the nail may result and infection may soon follow. Sometimes a small amount of pus can be seen draining from the area.

Ingrown nails may develop for many reasons. Some cases are congenital—the nail is just too large for the toe. Trauma, such as stubbing the toe or having the toe stepped on, may also cause an ingrown nail. However, the most common cause is tight shoe wear or improper grooming and trimming of the nail.

The anatomy of a toenail.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Ingrown toenails should be treated as soon as they are recognized. If they are recognized early (before infection sets in), home care may prevent the need for further treatment:

- Soak the foot in warm water 3-4 times daily.

- Keep the foot dry during the rest of the day.

- Wear comfortable shoes with adequate room for the toes. Consider wearing sandals until the condition clears up.

- You may take ibuprofen or acetaminophen for pain relief.

- If there is no improvement in 2-3 days, or if the condition worsens, call your doctor.

You may need to gently lift the edge of the ingrown toenail from its embedded position and insert some cotton or waxed dental floss between the nail and your skin. Change this packing every day.

Surgical Treatment

If excessive inflammation, swelling, pain and discharge are present, the toenail is probably infected and should be treated by a physician (see left image below). You may need to take oral antibiotics and the nail may need to be partially or completely removed (see middle image below). The doctor can surgically remove a portion of the nail, a portion of the underlying nail bed, some of the adjacent soft tissues and even a part of the growth center (see right image below).

Surgery is effective in eliminating the nail edge from growing inward and cutting into the fleshy folds as the toenail grows forward. Permanent removal of the nail may be advised for children with chronic, recurrent infected ingrown toenails.

If you are in a lot of pain and/or the infection keeps coming back, your doctor may remove part of your ingrown toenail (partial nail avulsion). Your toe is injected with an anesthetic and your doctor uses scissors to cut away the ingrown part of the toenail, taking care not to disturb the nail bed. An exposed nail bed may be very painful. Removing your whole ingrown toenail (complete nail plate avulsion) increases the likelihood your toenail will come back deformed. It may take 3-4 months for your nail to regrow.

Risk Factors

Unless the problem is congenital, the best way to prevent ingrown toenails is to protect the feet from trauma and to wear shoes and hosiery (socks) with adequate room for the toes. Nails should be cut straight across with a clean, sharp nail trimmer without tapering or rounding the corners. Trim the nails no shorter than the edge of the toe. Keep the feet clean and dry at all times.

Proper and improper toenail trimming.

Plantar Fasciitis and Bone Spurs

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of pain on the bottom of the heel. Plantar fasciitis occurs when the strong band of tissue that supports the arch of your foot becomes irritated and inflamed.

The plantar fascia is a long, thin ligament that lies directly beneath the skin on the bottom of your foot. It connects the heel to the front of your foot, and supports the arch of your foot.

Cause

The plantar fascia is designed to absorb the high stresses and strains we place on our feet. But, sometimes, too much pressure damages or tears the tissues. The body’s natural response to injury is inflammation, which results in the heel pain and stiffness of plantar fasciitis.

Risk Factors

In most cases, plantar fasciitis develops without a specific, identifiable reason. There are, however, many factors that can make you more prone to the condition:

- Tighter calf muscles that make it difficult to flex your foot and bring your toes up toward your shin

- Obesity

- Very high arch

- Repetitive impact activity (running/sports)

- New or increased activity

Heel Spurs

Although many people with plantar fasciitis have heel spurs, spurs are not the cause of plantar fasciitis pain. One out of 10 people has heel spurs, but only 1 out of 20 people (5%) with heel spurs has foot pain. Because the spur is not the cause of plantar fasciitis, the pain can be treated without removing the spur.

Heel spurs do not cause plantar fasciitis pain.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of plantar fasciitis include:

- Pain on the bottom of the foot near the heel

- Pain with the first few steps after getting out of bed in the morning, or after a long period of rest, such as after a long car ride. The pain subsides after a few minutes of walking

- Greater pain after (not during) exercise or activity

Examination

After you describe your symptoms and discuss your concerns, your doctor will examine your foot. Your doctor will look for these signs:

- A high arch

- An area of maximum tenderness on the bottom of your foot, just in front of your heel bone

- Pain that gets worse when you flex your foot and the doctor pushes on the plantar fascia. The pain improves when you point your toes down

- Limited “up” motion of your ankle

Tests

Your doctor may order imaging tests to help make sure your heel pain is caused by plantar fasciitis and not another problem.

X-rays

X-rays provide clear images of bones. They are useful in ruling out other causes of heel pain, such as fractures or arthritis. Heel spurs can be seen on an x-ray.

Other Imaging Tests

Other imaging tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound, are not routinely used to diagnose plantar fasciitis. They are rarely ordered. An MRI scan may be used if the heel pain is not relieved by initial treatment methods.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

More than 90% of patients with plantar fasciitis will improve within 10 months of starting simple treatment methods.

Rest. Decreasing or even stopping the activities that make the pain worse is the first step in reducing the pain. You may need to stop athletic activities where your feet pound on hard surfaces (for example, running or step aerobics).

Ice. Rolling your foot over a cold water bottle or ice for 20 minutes is effective. This can be done 3 to 4 times a day.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Drugs such as ibuprofen or naproxen reduce pain and inflammation. Using the medication for more than 1 month should be reviewed with your primary care doctor.

Exercise. Plantar fasciitis is aggravated by tight muscles in your feet and calves. Stretching your calves and plantar fascia is the most effective way to relieve the pain that comes with this condition.

- Calf stretch

Lean forward against a wall with one knee straight and the heel on the ground. Place the other leg in front, with the knee bent. To stretch the calf muscles and the heel cord, push your hips toward the wall in a controlled fashion. Hold the position for 10 seconds and relax. Repeat this exercise 20 times for each foot. A strong pull in the calf should be felt during the stretch.

- Plantar fascia stretch

This stretch is performed in the seated position. Cross your affected foot over the knee of your other leg. Grasp the toes of your painful foot and slowly pull them toward you in a controlled fashion. If it is difficult to reach your foot, wrap a towel around your big toe to help pull your toes toward you. Place your other hand along the plantar fascia. The fascia should feel like a tight band along the bottom of your foot when stretched. Hold the stretch for 10 seconds. Repeat it 20 times for each foot. This exercise is best done in the morning before standing or walking.

Cortisone injections. Cortisone, a type of steroid, is a powerful anti-inflammatory medication. It can be injected into the plantar fascia to reduce inflammation and pain. Your doctor may limit your injections. Multiple steroid injections can cause the plantar fascia to rupture (tear), which can lead to a flat foot and chronic pain.

Soft heel pads can provide extra support.

Supportive shoes and orthotics. Shoes with thick soles and extra cushioning can reduce pain with standing and walking. As you step and your heel strikes the ground, a significant amount of tension is placed on the fascia, which causes microtrauma (tiny tears in the tissue). A cushioned shoe or insert reduces this tension and the microtrauma that occurs with every step. Soft silicone heel pads are inexpensive and work by elevating and cushioning your heel. Pre-made or custom orthotics (shoe inserts) are also helpful.

Night splints. Most people sleep with their feet pointed down. This relaxes the plantar fascia and is one of the reasons for morning heel pain. A night splint stretches the plantar fascia while you sleep. Although it can be difficult to sleep with, a night splint is very effective and does not have to be used once the pain is gone.

Physical therapy. Your doctor may suggest that you work with a physical therapist on an exercise program that focuses on stretching your calf muscles and plantar fascia. In addition to exercises like the ones mentioned above, a physical therapy program may involve specialized ice treatments, massage, and medication to decrease inflammation around the plantar fascia.

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT). During this procedure, high-energy shockwave impulses stimulate the healing process in damaged plantar fascia tissue. ESWT has not shown consistent results and, therefore, is not commonly performed.

ESWT is noninvasive—it does not require a surgical incision. Because of the minimal risk involved, ESWT is sometimes tried before surgery is considered.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is considered only after 12 months of aggressive nonsurgical treatment.

Gastrocnemius recession. This is a surgical lengthening of the calf (gastrocnemius) muscles. Because tight calf muscles place increased stress on the plantar fascia, this procedure is useful for patients who still have difficulty flexing their feet, despite a year of calf stretches.

In gastrocnemius recession, one of the two muscles that make up the calf is lengthened to increase the motion of the ankle. The procedure can be performed with a traditional, open incision or with a smaller incision and an endoscope, an instrument that contains a small camera. Your doctor will discuss the procedure that best meets your needs.

Complication rates for gastrocnemius recession are low, but can include nerve damage.

Plantar fascia release. If you have a normal range of ankle motion and continued heel pain, your doctor may recommend a partial release procedure. During surgery, the plantar fascia ligament is partially cut to relieve tension in the tissue. If you have a large bone spur, it will be removed, as well. Although the surgery can be performed endoscopically, it is more difficult than with an open incision. In addition, endoscopy has a higher risk of nerve damage.

Complications. The most common complications of release surgery include incomplete relief of pain and nerve damage.

Recovery. Most patients have good results from surgery. However, because surgery can result in chronic pain and dissatisfaction, it is recommended only after all nonsurgical measures have been exhausted.

Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction

Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction is one of the most common problems of the foot and ankle. It occurs when the posterior tibial tendon becomes inflamed or torn. As a result, the tendon may not be able to provide stability and support for the arch of the foot, resulting in flatfoot.

Most patients can be treated without surgery, using orthotics and braces. If orthotics and braces do not provide relief, surgery can be an effective way to help with the pain. Surgery might be as simple as removing the inflamed tissue or repairing a simple tear. However, more often than not, surgery is very involved, and many patients will notice some limitation in activity after surgery.

The posterior tibial tendon is one of the most important tendons of the leg. A tendon attaches muscles to bones, and the posterior tibial tendon attaches the calf muscle to the bones on the inside of the foot. The main function of the tendon is to hold up the arch and support the foot when walking.

The posterior tibial tendon attaches the calf muscle to the bones on the inside of the foot.

Cause

An acute injury, such as from a fall, can tear the posterior tibial tendon or cause it to become inflamed. The tendon can also tear due to overuse. For example, people who do high-impact sports, such as basketball, tennis, or soccer, may have tears of the tendon from repetitive use. Once the tendon becomes inflamed or torn, the arch will slowly fall (collapse) over time.

Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction is more common in women and in people older than 40 years of age. Additional risk factors include obesity, diabetes, and hypertension.

Symptoms

- Pain along the inside of the foot and ankle, where the tendon lies. This may or may not be associated with swelling in the area.

- Pain that is worse with activity. High-intensity or high-impact activities, such as running, can be very difficult. Some patients can have trouble walking or standing for a long time.

- Pain on the outside of the ankle. When the foot collapses, the heel bone may shift to a new position outwards. This can put pressure on the outside ankle bone. The same type of pain is found in arthritis in the back of the foot.

The most common location of pain is along the course of the posterior tibial tendon (yellow line), which travels along the back and inside of the foot and ankle.

Examination

Medical History and Physical Examination

This patient has posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with a flatfoot deformity. (Left) The front of her foot points outward. (Right) The “too many toes” sign. Even the big toe can be seen from the back of this patient’s foot.

Your doctor will take a complete medical history and ask about your symptoms. During the foot and ankle examination, your doctor will check whether these signs are present.

- Swelling along the posterior tibial tendon. This swelling is from the lower leg to the inside of the foot and ankle.

- A change in the shape of the foot. The heel may be tilted outward and the arch will have collapsed.

- “Too many toes” sign. When looking at the heel from the back of the patient, usually only the fifth toe and half of the fourth toe are seen. In a flatfoot deformity, more of the little toe can be seen.

This patient is able to perform a single limb heel rise on the right leg.

- “Single limb heel rise” test. Being able to stand on one leg and come up on “tiptoes” requires a healthy posterior tibial tendon. When a patient cannot stand on one leg and raise the heel, it suggests a problem with the posterior tibial tendon.

- Limited flexibility. The doctor may try to move the foot from side to side. The treatment plan for posterior tibial tendon tears varies depending on the flexibility of the foot. If there is no motion or if it is limited, there will need to be a different treatment than with a flexible foot.

- The range of motion of the ankle is affected. Upward motion of the ankle (dorsiflexion) can be limited in flatfoot. The limited motion is tied to tightness of the calf muscles.

Imaging Tests

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

X-rays. These imaging tests provide detailed pictures of dense structures, like bone. They are useful to detect arthritis. If surgery is needed, they help the doctor make measurements to determine what surgery would most helpful.

(Top) An x-ray of a normal foot. Note that the lines are parallel, indicating a normal arch. (Bottom) In this x-ray the lines diverge, which is consistent with flatfoot deformity.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These studies can create images of soft tissues like the tendons and muscles. An MRI may be ordered if the diagnosis is in doubt.

Computerized tomography scan (CT Scan). These scans are more detailed than x-rays. They create cross-section images of the foot and ankle. Because arthritis of the back of the foot has similar symptoms to posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, a CT scan may be ordered to look for arthritis.

Ultrasound. An ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves that echo off the body. This creates a picture of the bone and tissue. Sometimes more information is needed to make a diagnosis. An ultrasound can be ordered to show the posterior tibial tendon.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Symptoms will be relieved in most patients with appropriate nonsurgical treatment. Pain may last longer than 3 months even with early treatment. For patients who have had pain for many months, it is not uncommon for the pain to last another 6 months after treatment starts.

Rest

Decreasing or even stopping activities that worsen the pain is the first step. Switching to low-impact exercise is helpful. Biking, elliptical machines, or swimming do not put a large impact load on the foot, and are generally tolerated by most patients.

Ice

Apply cold packs on the most painful area of the posterior tibial tendon for 20 minutes at a time, 3 or 4 times a day to keep down swelling. Do not apply ice directly to the skin. Placing ice over the tendon immediately after completing an exercise helps to decrease the inflammation around the tendon.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Medication

Drugs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, reduce pain and inflammation. Taking such medications about a half of an hour before an exercise activity helps to limit inflammation around the tendon. The thickening of the tendon that is present is degenerated tendon. It will not go away with medication. Talk with your primary care doctor if the medication is used for more than 1 month.

Immobilization

A short leg cast or walking boot may be used for 6 to 8 weeks. This allows the tendon to rest and the swelling to go down. However, a cast causes the other muscles of the leg to atrophy (decrease in strength) and thus is only used if no other conservative treatment works.

Orthotics

Most people can be helped with orthotics and braces. An orthotic is a shoe insert. It is the most common nonsurgical treatment for a flatfoot. An over-the-counter orthotic may be enough for patients with a mild change in the shape of the foot. A custom orthotic is required in patients who have moderate to severe changes in the shape of the foot. The custom orthotic is more costly, but it allows the doctor to better control the position the foot.

Braces

A lace-up ankle brace may help mild to moderate flatfoot. The brace would support the joints of the back of the foot and take tension off of the tendon. A custom-molded leather brace is needed in severe flatfoot that is stiff or arthritic. The brace can help some patients avoid surgery.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy that strengthens the tendon can help patients with mild to moderate disease of the posterior tibial tendon.

Steroid Injection

Cortisone is a very powerful anti-inflammatory medicine that your doctor may consider injecting around the tendon. A cortisone injection into the posterior tibial tendon is not normally done. It carries a risk of tendon rupture. Discuss this risk with your doctor before getting an injection.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery should only be done if the pain does not get better after 6 months of appropriate treatment. The type of surgery depends on where tendonitis is located and how much the tendon is damaged. Surgical reconstruction can be extremely complex. The following is a list of the more commonly used operations. Additional procedures may also be required.

Gastrocnemius Recession or Lengthening of the Achilles Tendon

This is a surgical lengthening of the calf muscles. It is useful in patients who have limited ability to move the ankle up. This surgery can help prevent flatfoot from returning, but does create some weakness with pushing off and climbing stairs. Complication rates are low but can include nerve damage and weakness. This surgery is typically performed together with other techniques for treating flatfoot.

Tenosynovectomy (Cleaning the Tendon)

This surgery is used when there is very mild disease, the shape of the foot has not changed, and there is pain and swelling over the tendon. The surgeon will clean away and remove the inflamed tissue (synovium) surrounding the tendon. This can be performed alone or in addition to other procedures. The main risk of this surgery is that the tendon may continue to degenerate and the pain may return.

Tendon Transfer

Tendon transfer can be done in flexible flatfoot to recreate the function of the damaged posterior tibial tendon. In this procedure, the diseased posterior tibial tendon is removed and replaced with another tendon from the foot, or, if the disease is not too significant in the posterior tibial tendon, the transferred tendon is attached to the preserved (not removed) posterior tibial tendon.

One of two possible tendons are commonly used to replace the posterior tibial tendon. One tendon helps the big toe point down and the other one helps the little toes move down. After the transfer, the toes will still be able to move and most patients will not notice a change in how they walk.

Although the transferred tendon can substitute for the posterior tibial tendon, the foot still is not normal. Some people may not be able to run or return to competitive sports after surgery. Patients who need tendon transfer surgery are typically not able to participate in many sports activities before surgery because of pain and tendon disease.

Osteotomy (Cutting and Shifting Bones)

An osteotomy can change the shape of a flexible flatfoot to recreate a more “normal” arch shape. One or two bone cuts may be required, typically of the heel bone (calcaneus).

If flatfoot is severe, a bone graft may be needed. The bone graft will lengthen the outside of the foot. Other bones in the middle of the foot also may be involved. They may be cut or fused to help support the arch and prevent the flatfoot from returning. Screws or plates hold the bones in places while they heal.

X-ray of a foot as viewed from the side in a patient with a more severe deformity. This patient required fusion of the middle of the foot in addition to a tendon transfer and cut in the heel bone.

Fusion

Sometimes flatfoot is stiff or there is also arthritis in the back of the foot. In these cases, the foot will not be flexible enough to be treated successfully with bone cuts and tendon transfers. Fusion (arthrodesis) of a joint or joints in the back of the foot is used to realign the foot and make it more “normal” shaped and remove any arthritis. Fusion involves removing any remaining cartilage in the joint. Over time, this lets the body “glue” the joints together so that they become one large bone without a joint, which eliminates joint pain. Screws or plates hold the bones in places while they heal.

This x-ray shows a very stiff flatfoot deformity. A fusion of the three joints in the back of the foot is required and can successfully recreate the arch and allow restoration of function.

Side-to-side motion is lost after this operation. Patients who typically need this surgery do not have a lot of motion and will see an improvement in the way they walk. The pain they may experience on the outside of the ankle joint will be gone due to permanent realignment of the foot. The up and down motion of the ankle is not greatly affected. With any fusion, the body may fail to “glue” the bones together. This may require another operation.

Complications

The most common complication is that pain is not completely relieved. Nonunion (failure of the body to “glue” the bones together) can be a complication with both osteotomies and fusions. Wound infection is a possible complication, as well.

Surgical Outcome

Most patients have good results from surgery. The main factors that determine surgical outcome are the amount of motion possible before surgery and the severity of the flatfoot. The more severe the problem, the longer the recovery time and the less likely a patient will be able to return to sports. In many patients, it may be 12 months before there is any great improvement in pain.

Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Foot and Ankle

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic disease that attacks multiple joints throughout the body. It most often starts in the small joints of the hands and feet, and usually affects the same joints on both sides of the body.

More than 90% of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) develop symptoms in the foot and ankle over the course of the disease.

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease. This means that the immune system attacks its own tissues. In RA, the defenses that protect the body from infection instead damage normal tissue (such as cartilage and ligaments) and soften bone.

How It Happens

The joints of your body are covered with a lining — called synovium — that lubricates the joint and makes it easier to move. Rheumatoid arthritis causes an overactivity of this lining. It swells and becomes inflamed, destroying the joint, as well as the ligaments and other tissues that support it. Weakened ligaments can cause joint deformities — such as claw toe or hammer toe. Softening of the bone (osteopenia) can result in stress fractures and collapse of bone.

Rheumatoid arthritis is not an isolated disease of the bones and joints. It affects tissues throughout the body, causing damage to the blood vessels, nerves, and tendons. Deformities of the hands and feet are the more obvious signs of RA. In about 20% of patients, foot and ankle symptoms are the first signs of the disease.

In RA, the lining of the joint swells and becomes inflamed. This slowly destroys the joint.

Statistics

Rheumatoid arthritis affects approximately 1% of the population. Women are affected more often than men, with a ratio of up to 3 to 1. Symptoms most commonly develop between the ages of 40 and 60.

Cause

The exact cause of RA is not known. There may be a genetic reason — some people may be more likely to develop the disease because of family heredity. However, doctors suspect that it takes a chemical or environmental “trigger” to activate the disease in people who genetically inherit RA.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms are pain, swelling, and stiffness. Unlike osteoarthritis, which typically affects one specific joint, symptoms of RA usually appear in both feet, affecting the same joints on each foot.

Anatomy of the foot and ankle.

Ankle

Difficulty with inclines (ramps) and stairs are the early signs of ankle involvement. As the disease progresses, simple walking and standing can become painful.

Hindfoot (Heel Region of the Foot)

The main function of the hindfoot is to perform the side-to-side motion of the foot. Difficulty walking on uneven ground, grass, or gravel are the initial signs. Pain is common just beneath the fibula (the smaller lower leg bone) on the outside of the foot.

As the disease progresses, the alignment of the foot may shift as the bones move out of their normal positions. This can result in a flatfoot deformity. Pain and discomfort may be felt along the posterior tibial tendon (main tendon that supports the arch) on the inside of the ankle, or on the outside of the ankle beneath the fibula.

Midfoot (Top of the Foot)

With RA, the ligaments that support the midfoot become weakened and the arch collapses. With loss of the arch, the foot commonly collapses and the front of the foot points outward. RA also damages the cartilage, causing arthritic pain that is present with or without shoes. Over time, the shape of the foot can change because the structures that support it degenerate. This can create a large bony prominence (bump) on the arch. All of these changes in the shape of the foot can make it very difficult to wear shoes.

This x-ray shows signs of RA of the midfoot. Note that the front of the foot points outward and there is a large bump on the inside and bottom of the foot.

Forefoot (Toes and Ball of the Foot)

The changes that occur to the front of the foot are unique to patients with RA. These problems include bunions, claw toes, and pain under the ball of the foot (metatarsalgia). Although, each individual deformity is common, it is the combination of deformities that compounds the problem.

People with RA can experience a combination of common foot problems, such as bunions and clawtoe.

The bunion is typically severe and the big toe commonly crosses over the second toe.

There can also be very painful bumps on the ball of the foot, creating calluses. The bumps develop when bones in the middle of the foot (midfoot) are pushed down from joint dislocations in the toes. The dislocations of the lesser toes (toes two through five) cause them to become very prominent on the top of the foot. This creates clawtoes and makes it very difficult to wear shoes. In severe situations, ulcers can form from the abnormal pressure.

Severe claw toes can become fixed and rigid. They do not move when in a shoe. The extra pressure from the top of the shoe can cause severe pain and can damage the skin.

Examination

Medical History and Physical Examination

After listening to your symptoms and discussing your general health and medical history, your doctor will examine your foot and ankle.

Skin. The location of callouses indicate areas of abnormal pressure on the foot. The most common location is on the ball of the foot (the underside of the forefoot). If the middle of the foot is involved, there may be a large prominence on the inside and bottom of the foot. This can cause callouses.

Foot shape. Your doctor will look for specific deformities, such as bunions, claw toes, and flat feet.

Flexibility. In the early stages of RA, the joints will typically still have movement. As arthritis progresses and there is a total loss of cartilage, the joints become very stiff. Whether there is motion within the joints will influence treatment options.

Tenderness to pressure. Although applying pressure to an already sensitive foot can be very uncomfortable, it is critical that your doctor identify the areas of the foot and ankle that are causing the pain. By applying gentle pressure at specific joints your doctor can determine which joints have symptoms and need treatment. The areas on the x-ray that look abnormal are not always the same ones that are causing the pain.

Imaging Tests

Other tests that your doctor may order to help confirm your diagnosis include:

X-rays. This test creates images of dense structures, like bone. It will show your doctor the position of the bones. The x-rays can be used by your doctor to make measurements of the alignment of the bones and joint spaces, which will help your doctor determine what surgery would best.

Computerized tomography (CT) scan. When the deformity is severe, the shape of the foot can be abnormal enough to make it difficult to determine which joints have been affected and the extent of the disease. CT scans allow your doctor to more closely examine each joint for the presence of arthritis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. An MRI scan will show the soft tissues, including the ligaments and tendons. Your doctor can assess whether the tendon is inflamed (tendonitis) or torn (ruptured).

Rheumatology Referral

Your doctor may refer you to a rheumatologist if he or she suspects RA. Although your symptoms and the results from a physical examination and tests may be consistent with RA, a rheumatologist will be able to determine the specific diagnosis. There are other less common types of inflammatory arthritis that will be considered.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Although there is no cure for RA, there are many treatment options available to help people manage pain, stay active, and live fulfilling lives.

Rheumatoid arthritis is often treated by a team of healthcare professionals. These professionals may include rheumatologists, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and orthopaedic surgeons.

Although orthopaedic treatment may relieve symptoms, it will not stop the progression of the disease. Specific medicines called disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs are designed to stop the immune system from destroying the joints. The appropriate use of these medications is directed by a rheumatologist.

Orthopaedic treatment of RA depends on the location of the pain and the extent of cartilage damage. Many patients will have some symptom relief with appropriate nonsurgical treatment.

Rest

Limiting or stopping activities that make the pain worse is the first step in minimizing the pain. Biking, elliptical training machines, or swimming are exercise activities that allow patients to maintain their health without placing a large impact load on the foot.

Ice

Placing ice on the most painful area of the foot for 20 minutes is effective. This can be done 3 or 4 times a day. Ice application is best done right after you are done with a physical activity. Do not apply ice directly to your skin.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Medication

Drugs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, reduce pain and inflammation. In patients with RA, the use of these types of medications should be reviewed with your rheumatologist or medical doctor.

Orthotics

An orthotic (shoe insert) is a very effective tool to minimize the pressure from prominent bones in the foot. The orthotic will not be able to correct the shape of your foot. The primary goal is to minimize the pressure and decrease the pain and callous formation. This is more effective for deformity in the front and middle of the foot.

A custom-molded leather brace can be effective in minimizing the pain and discomfort from ankle and hindfoot arthritis.

For people with RA, hard or rigid orthotics generally cause too much pressure on the bone prominences, creating more pain. A custom orthotic is generally made of softer material and relieves pressure on the foot.

Braces

A lace-up ankle brace can be an effective treatment for mild to moderate pain in the back of the foot and the ankle. The brace supports the joints of the back of the foot and ankle. In patients with a severe flatfoot or a very stiff arthritic ankle, a custom-molded plastic or leather brace is needed. The brace can be a very effective device for some patients, allowing them to avoid surgery.

Steroid Injection

An injection of cortisone into the affected joint can help in the early stages of the disease. In many cases, a rheumatologist or medical doctor may also perform these injections. The steroid helps to reduce inflammation within the joint. The steroid injection is normally a temporary measure and will not stop the progression of the disease.

Surgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery depending upon the extent of cartilage damage and your response to nonsurgical options.

Fusion. Fusion of the affected joints is the most common type of surgery performed for RA. Fusion takes the two bones that form a joint and fuses them together to make one bone.

During the surgery, the joints are exposed and the remaining cartilage is removed. The two bones are then held together with screws or a combination of screws and plates. This prevents the bones from moving. During the healing process, the body grows new bone between the bones in these joints.

Because the joint is no longer intact, this surgery does limit joint motion. Limited joint motion may not be felt by the patient, depending on the joints fused. The midfoot joints often do not have much motion to begin with, and fusing them does not create increased stiffness. The ankle joint normally does have a lot of motion, and fusing it will be noticeable to the patient. By limiting motion, fusion reduces the pain.

Fusion can be a successful technique. However, because patients with RA also show damaged cartilage and loose ligaments, the success rate of this type of surgery is lower in patients with RA than in patients without RA. The use of newer generation medication can slow the progression of the disease and impact the type of surgeries that can be performed successfully.

Other surgeries. The front of the foot is where there are more surgical options for some patients. Surgeons can now perform joint sparing operations to correct the bunion and hammertoes in some patients. Your surgeon will review the most appropriate options for your case.

Ankle

Ankle fusion and total ankle replacement are the two primary surgical options for treating RA of the ankle. Both treatment options can be successful in minimizing the pain and discomfort in the ankle. The appropriate surgery is based upon multiple factors and is individualized for every patient.

The patient shown in these x-rays had arthritis of the hindfoot. It was treated by fusing all three joints of the hindfoot (triple fusion). An ankle replacement was also done in order to improve mobility and avoid the severe stiffness that would result from another ankle fusion. The ankle replacement implants can be seen here from the front and the side.

Patients with severe involvement of other joints around the heel or patients who have previously undergone a fusion on the other leg, may be more suited for ankle replacement. In addition, patients who have fusions within the same foot may be more suited for an ankle replacement.

Newer generation ankle replacement implants have shown promising early results. Ankle replacement implants have not yet been shown to be as long-lasting as those for the hip or knee, due to the fact that the newer generation of implants have not been available long enough to determine how long they will last.

These x-rays show an ankle fusion from the front and the side. The number and placement of screws and the use of a plate are dependent upon the surgeon’s technique.

Following ankle fusion, there is a loss of the up and down motion of the ankle. The up and down motion is transferred to the joints near the ankle. This creates a potential for pain in those joints, and possibly arthritis.

Patients are able to walk in shoes on flat, level ground without much difficulty after an ankle fusion, despite the loss of ankle motion. The joints in the foot next to the ankle joint allow for motion similar to the ankle joint, and help patients with fused ankle joints walk more normally.

Over time, the increased stress that is placed on the rest of the foot after an ankle fusion can lead to arthritis of the joints surrounding the ankle. This patient had pain in the subtalar joint (arrow) and required an additional fusion of that joint to minimize the pain. Increased stress on other joints is the most concerning problem following ankle fusion.

Hindfoot (Heel Region of the Foot)